ACE Merits Amicus Brief – U.S. Supreme Court

Parental Choice as a Human Right?

So much has been written about parental choice in education that it can sometimes feel like every article is just an iteration of every other. Occasionally, though, someone publishes a that examines the issue from a totally new (and totally unexpected) angle. Case in point: a recent Education Post article on school choice as a human right.

Folks cite all sorts of documents in support of or opposition to broad-spectrum choice in education—the U.S. Constitution, state constitutions, various statutes, regulations, founding documents, etc. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), however, is rarely among them. The United Nations doesn’t exactly wade into many debates over education policy.

Former teacher Joe Nathan argues in his article that choice supporters may be missing an important argument by failing to recognize Article 26 of the UDHR when advocating for expanded educational options. That article reads:

- Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

- Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

- Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

Nathan specifically highlights the third point, which flatly states that parents have a “prior right” to choose what type of education their children receive. That right stands equal among others with which we are all familiar: the right to free association, the right to fair and equitable legal systems, and the right to life, liberty, and security of person.

The declaration stops short of calling for specific policy solutions, but it is rather unequivocal in its call for parental empowerment. Given the breadth of language, it is surprising that Nathan goes on to say that he opposes private school choice programs. He cites two primary reasons for this opposition, one about faith-based education and one about admissions practices in schools receiving “public funds.” Through these points of contention, he seems to imply that choices should be limited to those provided in the public education sector (and even then, he opposes public magnet schools for certain types of children).

In point of fact, scholarship tax credit programs, which are the most widely used form of private school choice, rely solely on private funding rather than state money. But even setting aside that important caveat, I think Nathan misses the mark on this point.

The UDHR does not state that parents have a prior right to choose the type of “public” education their children will receive. It also does not state that parents should be free to choose among only secular options, or that schools with more rigorous admissions processes should be excluded. It says that parents have a prior right to make choices about “education,” period. If we’re talking about a broadly applicable human right, attempting to limit it or oppose certain iterations of it seems both dangerous and contrary to the spirit of the document being cited. After all, “prior rights” can’t be revoked or circumscribed. That’s kind of the point.

The UDHR itself seems to agree, stating specifically in Article 2 that the rights apply to everyone “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” It would be very difficult to argue that restricting the types of schools parents have a right to choose would not draw a “distinction of any kind” based on certain beliefs or opinions. Parents ought to have access to the educational options that work best for their children, full stop. Whether those options are provided in the public or private sectors is immaterial.

Setting aside specific policy disagreements, however, Nathan has done the choice debate a service by framing it in a different light. Now if you’ll excuse us, we have human rights to fight for.

Atlantic Article Misses the Mark on Education and Community

Almost no one would argue with the fact that schools play an integral role in their communities. But a recent article in The Atlantic argues that this role is limited to traditional public schools, and particularly public high schools. The article received a lot of attention, but it misses the mark in a few key ways. It’s time to set the record straight.

In the Atlantic piece, Assistant Professor of English Amy Lueck argues that “Public education and its traditions united communities. But ‘school choice’ could put that legacy at risk.” To support this argument, she offers up a variety of common American high school experiences: yearbooks, school dances, social interactions, sports, and other activities. She also focuses on the efforts of public high schools to drive civic knowledge and engagement.

All of these things are great, and there is no doubt that many public high schools live up to the image conjured by the article. Still, it’s hard to escape the fact that all the life experiences described in the Atlantic article also occur in private schools, sometimes to an even greater degree thanks to their typically smaller environments. In addition to this oversight, the article misses three critical points:

Private schools play an important role in building engaged citizens. Research tells us private schools often cultivate civic values and engagement to a greater degree than public schools. There is no empirical reason to believe that traditional public schools are better equipped to act as training grounds for the next generation of American citizens than private schools in the same communities. In fact, the existing evidence refutes that perspective. If one goal of education is to build strong, civically engaged community members, private school choice should be an important arrow in the quiver.

“Unification” is not always a good thing. That may sound sacrilegious, but it’s true. Perhaps one of the greatest failings in American education has been its tendency to isolate communities based on income and demographics. The Atlantic article briefly acknowledges the discriminatory history of American public education, but largely waves that history off as being reflective of “broader cultural values and practices” and the result of parents with means leaving to find better opportunities. It fails to seriously consider the fact that the issue is more fundamental to the design of “common schools,” or that school choice is largely intended to mitigate the segregation that still exists today. If you would like evidence of just how stratified American society is across different communities, spend some time with the Census Bureau’s new Opportunity Atlas.

Early data from ACE Scholarships indicate that providing access to private options can alter behaviors and expectations by exposing families to different peer groups and environments—and that’s exactly what we should want. Breaking down the walls between different communities and leveling the playing field is the primary objective of school choice. It should be the goal of the entire American education system. No idealized notion of communal education is worth a child’s life or future.

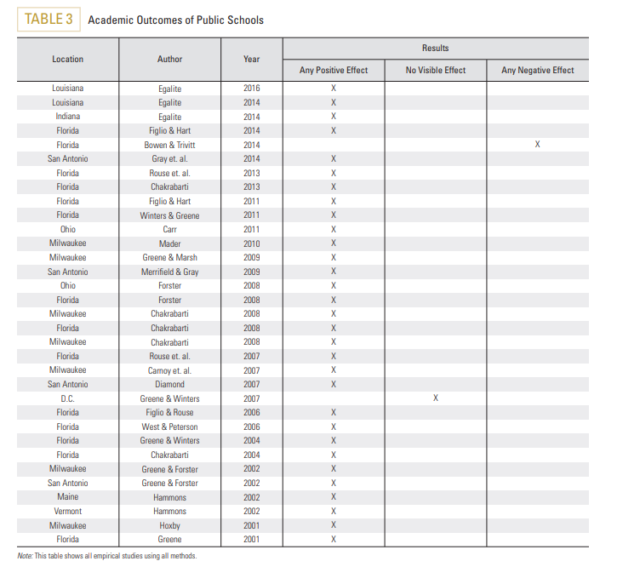

Public schools face little threat from private options. Private school choice programs as we currently think about them have existed since the first one passed in Wisconsin in 1990. Scholarship tax credit programs like those in which ACE participates have been around since 1997. Higher-education scholarship programs that allow students to attend private schools—Pell grants, GI Bill, etc.—have been around for even longer than that. If we were going to witness the destruction of public education as a result of access to private options, one would think we might have seen a move in that direction at this point. We haven’t. Instead, the vast majority of existing research indicates that K-12 private school choice programs improve the academic outcomes of public schools. See below for a rundown of that research.

Credit: EdChoice 2016

On the other hand, private schools very much face crowd-out from public schools, as evidenced by declining enrollment trends over the past several decades. Those declines are partially explained by the fact that lower-income families have increasingly found themselves unable to keep up with rising tuition costs. Considering that many of these private school networks have been serving their communities for hundreds of years, it seems that concerns about “putting legacies at risk” might be better focused on the private sector than on traditional public schools.

It’s great to celebrate the ability of schools to produce positive impacts in their communities. But we should keep the argument in line with reality and remember that no particular sector of education has a monopoly on this important work.