Almost no one would argue with the fact that schools play an integral role in their communities. But a recent article in The Atlantic argues that this role is limited to traditional public schools, and particularly public high schools. The article received a lot of attention, but it misses the mark in a few key ways. It’s time to set the record straight.

In the Atlantic piece, Assistant Professor of English Amy Lueck argues that “Public education and its traditions united communities. But ‘school choice’ could put that legacy at risk.” To support this argument, she offers up a variety of common American high school experiences: yearbooks, school dances, social interactions, sports, and other activities. She also focuses on the efforts of public high schools to drive civic knowledge and engagement.

All of these things are great, and there is no doubt that many public high schools live up to the image conjured by the article. Still, it’s hard to escape the fact that all the life experiences described in the Atlantic article also occur in private schools, sometimes to an even greater degree thanks to their typically smaller environments. In addition to this oversight, the article misses three critical points:

Private schools play an important role in building engaged citizens. Research tells us private schools often cultivate civic values and engagement to a greater degree than public schools. There is no empirical reason to believe that traditional public schools are better equipped to act as training grounds for the next generation of American citizens than private schools in the same communities. In fact, the existing evidence refutes that perspective. If one goal of education is to build strong, civically engaged community members, private school choice should be an important arrow in the quiver.

“Unification” is not always a good thing. That may sound sacrilegious, but it’s true. Perhaps one of the greatest failings in American education has been its tendency to isolate communities based on income and demographics. The Atlantic article briefly acknowledges the discriminatory history of American public education, but largely waves that history off as being reflective of “broader cultural values and practices” and the result of parents with means leaving to find better opportunities. It fails to seriously consider the fact that the issue is more fundamental to the design of “common schools,” or that school choice is largely intended to mitigate the segregation that still exists today. If you would like evidence of just how stratified American society is across different communities, spend some time with the Census Bureau’s new Opportunity Atlas.

Early data from ACE Scholarships indicate that providing access to private options can alter behaviors and expectations by exposing families to different peer groups and environments—and that’s exactly what we should want. Breaking down the walls between different communities and leveling the playing field is the primary objective of school choice. It should be the goal of the entire American education system. No idealized notion of communal education is worth a child’s life or future.

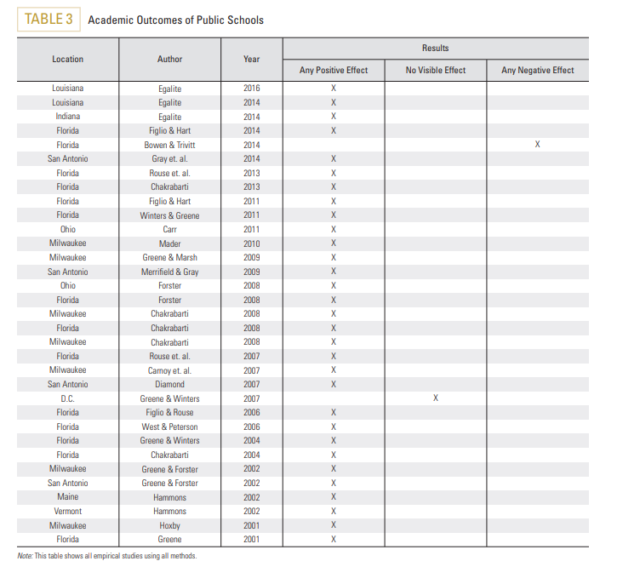

Public schools face little threat from private options. Private school choice programs as we currently think about them have existed since the first one passed in Wisconsin in 1990. Scholarship tax credit programs like those in which ACE participates have been around since 1997. Higher-education scholarship programs that allow students to attend private schools—Pell grants, GI Bill, etc.—have been around for even longer than that. If we were going to witness the destruction of public education as a result of access to private options, one would think we might have seen a move in that direction at this point. We haven’t. Instead, the vast majority of existing research indicates that K-12 private school choice programs improve the academic outcomes of public schools. See below for a rundown of that research.

Credit: EdChoice 2016

On the other hand, private schools very much face crowd-out from public schools, as evidenced by declining enrollment trends over the past several decades. Those declines are partially explained by the fact that lower-income families have increasingly found themselves unable to keep up with rising tuition costs. Considering that many of these private school networks have been serving their communities for hundreds of years, it seems that concerns about “putting legacies at risk” might be better focused on the private sector than on traditional public schools.

It’s great to celebrate the ability of schools to produce positive impacts in their communities. But we should keep the argument in line with reality and remember that no particular sector of education has a monopoly on this important work.